This post abstracts handling async tasks and come up with declarative linearized API model. Async tasks includes nested networking, nested animation and even nested multi-threading compute intensive code blocks. Async task is one of side effect programming technique.

Side effect is integral part of programming; mutating state, printing to screen/paper, asynctask to download JSON, keeping a running counter, locking/unlocking thread are all examples of side effect programming technique. Any useful programming language must provide a way to interact with side effects. This is how we build real world application. However, complexity increases as we increase side effect; for example, think how a view controller with 10 mutable properties is easier to reason, debug and maintain than a view controller with 20 mutable properties. Compare nested callback code to a normal code. Functional Programming (FP) and Imperative programming (IP) take different stance on tackling this issue at hand. IP uses callbacks while FP prefers monadic approach. We are interested to see monadic approach in this particular case.

Functional Programming takes monadic approach to hide the impurity behind a type and work with pure functions. Can we do the same in Swift?

We will do 3 things:

- Understand and know how to encapsulate async tasks (getting rid of callback hell)

- See how we can use this type to encapsulate and create declarative animation API.

- See how 30 lines can do all these above tasks.

As a side note, the monadic type that we will implement is popular as Promise or Future or Deferred on various texts. We will stick with Promise for this post.

The callback hell

Problem: Say you need to get string from This site and then from this amazing www.objc.io site for reasons you can think of.

Obviously, this looks familiar. Say I need to chain other sites only if the second on succeeds.

let session = URLSession(configuration: .default)

session.dataTask(with: kvurl) { (dataO, responseO, errorO) in

if let data = dataO, errorO == nil {

session.dataTask(with: objciourl) { (data2O, response2O, error2O) in

if let data2 = data2O, error2O == nil {

// doSomething

}

}.resume()

}

}.resume()

Thinking linearly is easy and preferred. The above code breaks the linear progressive thinking. Code exposes the branching/completion or nested model.

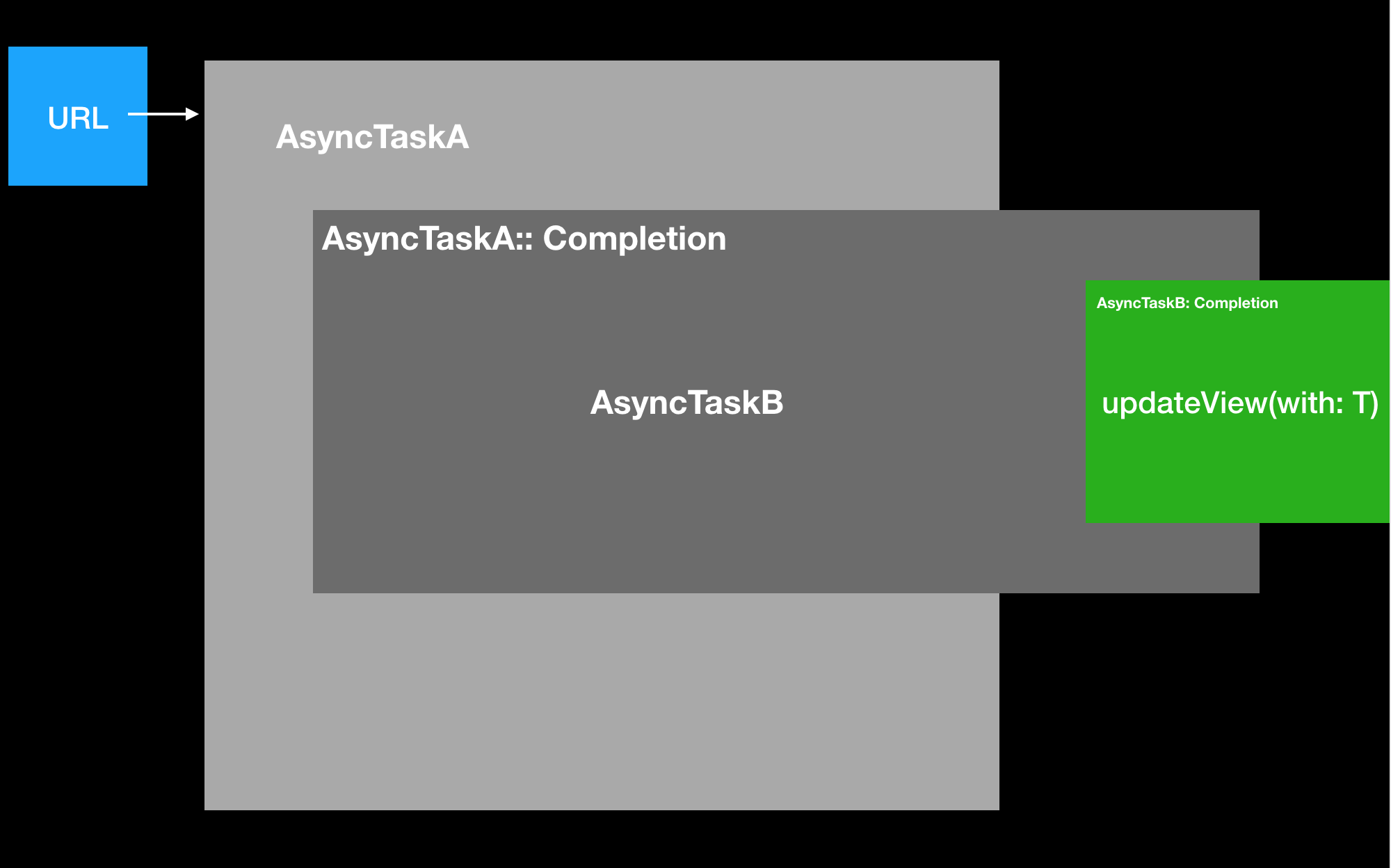

This kind of nested callback baked code gets into release and when we want to add 1 more request down the line; we add 1 more nesting. See the picture; we go off the screen. The real trouble here is; Its a lot of manual, concerned and fragile process of tackling repeated nesting. See the 2 resume() above. See the 2 places where we need to handle error/success. Is it really DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself)?

A immediate solution to clean up is to move the nested network call and supply via a completion handler. It’s a step in our direction but to me it doesn’t provide a good enough abstraction. One can also break nesting into functions to leave minimum impact to readability but still the code has repeating parts and exposes its nature of async.

Our final solution:

Network(kvurl).get().bind { _ in

return Network(objciourl).get()

}.then { _ in

/* do something */

}.execute()

Thats it!. Don’t worry about bind and then. We shall see they are very simple functions too.

Let me show you yet another example:

Nested animation!! (The imperative)

UIView.animate(withDuration: 2, animations: {

view.backgroundColor = .red

}) { _ in

UIView.animate(withDuration: 3, animations: {

view.backgroundColor = .green

}) { _ in

UIView.animate(withDuration: 4) {

view.backgroundColor = .purple

}

}

}

See that innermost animation block. This is just a trivial example. You might nest 10 level deep or live with 3. You got the point: we went literally deep. Our code has repeating UIView.animateWith.... and brackets.

Declarative Animations!!! (The Functional)

view.animate(with: 2) {

$0.backgroundColor = .red

}.animate(with: 3) {

$0.backgroundColor = .green

}.animate(with: 4) {

$0.backgroundColor = .purple

}.execute()

Think how the second code would look if you had to do 10 chained animations. Just more lines, not nesting!

One could step up one more and write a sequence function to execute animation tokens from an array in order like such.

Promise(view).animate(with: [

AnimationToken(duration: 4) { $0.backgroundColor = .white },

AnimationToken(duration: 2) { $0.backgroundColor = .green },

]).execute()

If you are interested into declarative animation then I highly suggest John Sundell’s recent Blog post where he takes you from ground up to build declarative animation API. My aim here was to show, how you can use this Promise type to reach to similar ground.

The only price you pay to do such declarative programming is either language to support directly or third party libraries which you can embed and forget about how it works. The cost you pay for if you want to use Promise / Future is to understand them.

There exists numerous third party libraries that provide this feature of linear progression of async tasks and more features. It’s easy to get lost in details of feature laden library when all you want is to understand the core. That’s exactly why, I find it more interesting to implement them myself and with a different twist.

Enter Promise (It shall be monadic)

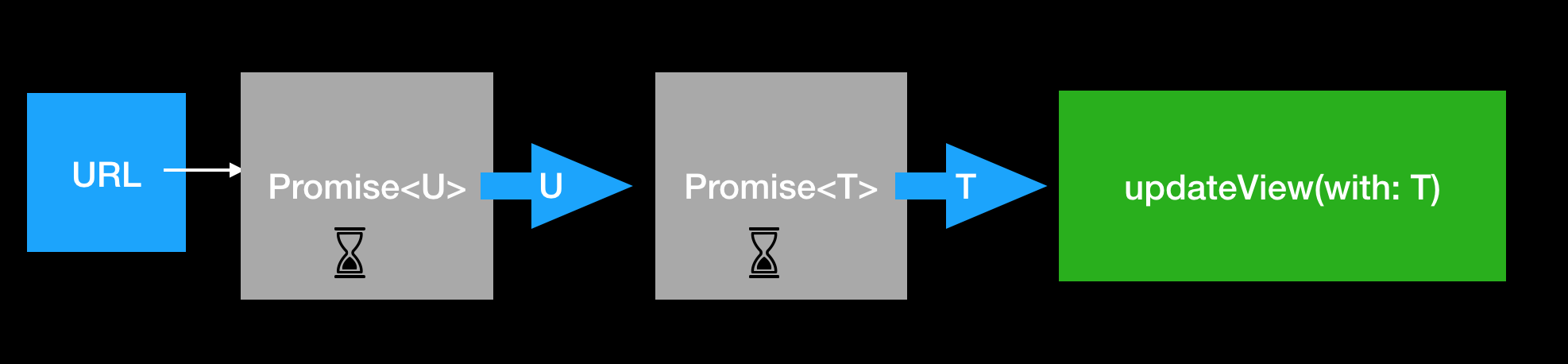

A promise is a return type of a async task. All it represents is the type of the eventual result it will have, immediately.

Think of it as a box which will provide a liquid pipe to the caller. The caller knows what kind of liquid he/she will get when the box is filled. Maybe water, whiskey or beer. This is the BOX’s promise (the liquid type). While the box might take time to fill before pushing to caller, the caller can act as if he already has such liquid. For instance, prepare the right container to store the liquid when it comes.

In our case, a async task can produce a promise. The pipe will be the function then through which you supply what work you will do when you get the liquid (type of result).

There it is, in the entirety!

public struct Promise<T> {

public typealias Completion = (T) -> Void

var aTask: ((Completion?) -> Void)? = nil

public init(_ task: @escaping ((Completion?) -> Void)) {

self.aTask = task

}

@discardableResult public func then<U>(_ transform: @escaping (T) -> U) -> Promise<U> {

return Promise<U>{ upcomingCompletion in

self.aTask?() { tk in

let transformed = transform(tk)

upcomingCompletion?(transformed)

}

}

}

public func execute() {

aTask?(nil)

}

}

That’s almost it! I removed the documentation which you can find at Github MPromise Repo.

Couple of points worth noting:

- Promise is a Value type.

- Promise is Generic in terms of T where T represents the type of eventual value that the task produces.

- Initializer, is just a closure which represents usually async task that will call into the completion parameter with proper type when it is done.

thenis a decorator (in reverse) that wraps initial task inside another one. Essentially, this is what we were doing manually with nested callbacks.- Finally, nothing gets executed until

execute()is invoked on the promise.

Promise contains expression. This is a subtle design choice I made on this type. The implication being we can build a big expression that doesn’t necessarily have to evaluated when the program sees. We can store it in a property, pass to a function or copy it. We can also call the execute multiple times. The compiler then can also choose to optimize the expression when possible. One can compose 2 promises in ways never thought. And all this is good because a Promise is a Value type.

Lets see how we can construct a Promise to start with.

The constructor

public class Network {

public init(_ url: URL) {

self.url = url

}

public func get() -> Promise<Result<Data>> {

return Promise { aCompletion in

let session = URLSession(configuration: .default)

let task = session.dataTask(with: self.url) { (data, response, error) in

if let d = data, error == nil {

aCompletion?(.success(d))

} else if let e = error {

aCompletion?(.failure(e))

} else {

aCompletion?(.failure(NetworkError.unknown))

}

}

task.resume()

}

}

}

Just the same old networking code. However, notice the Promise we return immediately. This allows us to work in linear progression mode while Promise hides the asynchronous part from us. Remember, this is not anything new. Its just perspective change, right!

The animation promise

extension UIView {

func animate(duration: TimeInterval, animation: @escaping (UIView) -> Void) -> Promise<UIView> {

return Promise<UIView> { aC in

UIView.animate(withDuration: duration, animations: {

animation(self)

}) { finished in

if finished {

aC?(self)

}

}

}

}

}

which allows one to then do these things:

view.animate(duration: 2) {

$0.backgroundColor = .yellow

}.then { view -> UIView in

view.animate(duration: 3) {

$0.backgroundColor = .green

}.execute()

return view

}.then {

$0.animate(duration: 4) {

$0.backgroundColor = .purple

}.execute()

}.execute()

A negligible improvement. Repetition of execute() and nesting of promise is a remarkable sign we have work to do.

Currently then takes UIView, animates and return UIView. Chained then (the second one) is called immediately without waiting for the animation inside to finish.

then :: ((T) -> U) -> Promise<U>

To be able to wait until the inner animation is done, we need to wrap the inner animation into a promise and return that promise instead of UIView. But, we will have a double layered Promise for the next then.

then :: ((T) -> Promise<A>) -> Promise<Promise<A>> //U is Promise<A>

view.animate(duration: 2) {

$0.backgroundColor = .red

}.then { view -> Promise<UIView> in

return view.animate(duration: 3) {

$0.backgroundColor = .green

}

}.then { promise -> Void in

promise.then {

$0.animate(duration: 4) {

$0.backgroundColor = .purple

}.execute()

}.execute()

}.execute()

Didn’t help get rid of the multiple execute(). Let’s take a another approach of generalizing this.

How can we semantically differentiate these two ways of calling then?

then :: ((T) -> U) -> Promise<U>

then2 :: ((T) -> Promise<U>) -> Promise<Promise<U>>

Remember (T) -> U doesn’t refrain one from specializing as UIView -> Promise<UIView>. When then2 is used, the second chained block has to extract the promise and then only can do his real work. This is exactly what happened up there. How can we get this semantics?

then2 :: ((T) -> Promise<U>) -> Promise<U>

Now a way to solve it is by flattening/ joining the nested Promises. Similar to the flatMap approach taken by Collection in swift.

join :: Promise<Promise<A>> -> Promise<A>

This is what monad’s bind function signature looks like. Lets rename this then2 to bind.

bind :: ((T) -> Promise<U>) -> Promise<U>

Lets review the implementation details.

Enter Monadic Promise.

public func bind<U>(_ transform: @escaping (T) -> Promise<U>) -> Promise<U> {

let transformed = then(transform) //1. Promise<Promise<U>>

return Promise.join(transformed) //2. Promise<U>

}

static private func join<A>(_ input: Promise<Promise<A>>) -> Promise<A> {

return Promise<A>{ aCompletion in

input.then { innerPromise in

innerPromise.then { innerValue in

aCompletion?(innerValue)

}.execute()

}.execute()

}

}

Its important to note the type signature of bind and then.

`then :: ((T) -> U) -> Promise<U>`

`bind :: ((T) -> Promise<U>) -> Promise<U>`

bind is a generalization which uses join function that takes care of flattening double layered promise into a single layered. Now we can chain the next then in usual way.

Our animation API can now be in terms of bind:

view.animate(duration: 2) {

$0.backgroundColor = .red

}.bind {

return $0.animate(duration: 3) {

$0.backgroundColor = .green

}

}.bind {

return $0.animate(duration: 4) {

$0.backgroundColor = .purple

}

}

Nice!!! Can we make it more readable. Sure we do!

extension Promise where T == UIView {

func animate(with duration: TimeInterval, animation: @escaping (UIView) -> Void) -> Promise<UIView> {

return self.bind { view in

view.animate(duration: duration, animation: animation)

}

}

}

Note:

- We now generalize over the repeating code

return $0.animate(duration: ) { }

Then our animation code looks like these:

view.animate(with: 2) {

$0.backgroundColor = .red

}.animate(with: 3) {

$0.backgroundColor = .green

}.animate(with: 4) {

$0.backgroundColor = .purple

}.execute()

Isn’t that declarative? I bet! 👍🤓

Summarizing:

- The entire

Promise<T>is then the below code:

public struct Promise<T> {

public typealias Completion = (T) -> Void

var aTask: ((Completion?) -> Void)? = nil

public init(_ task: @escaping ((Completion?) -> Void)) {

self.aTask = task

}

@discardableResult public func then<U>(_ transform: @escaping (T) -> U) -> Promise<U> {

return Promise<U>{ upcomingCompletion in

self.aTask?() { tk in

let transformed = transform(tk)

upcomingCompletion?(transformed)

}

}

}

public func bind<U>(_ transform: @escaping (T) -> Promise<U>) -> Promise<U> {

let transformed = then(transform) //1. Promise<Promise<U>>

return Promise.join(transformed) //2. Promise<U>

}

static private func join<A>(_ input: Promise<Promise<A>>) -> Promise<A> {

return Promise<A>{ aCompletion in

input.then { innerPromise in

innerPromise.then { innerValue in

aCompletion?(innerValue)

}.execute()

}.execute()

}

}

public func execute() {

aTask?(nil)

}

}

- Given this basic type, we can linearize async task (networking and animation to name a few).

- Hopefully, one can appreciate how simple generalization can be powerful force to allow expressive and declarative programming framework.

- Other approaches people came with are Deferred, Future and PromiseKit. They all allow one to generalize async code in one way or another. They do provide other features like dispatching on certain threads, catching error and other utility functions. The core code is tucked away and has larger surface area than this monadic approach we took. To me thats a big win.

1 more thing

- What is a Monad? How is

Promise<T>a Monad?

In fact, Promise<T> is a complete Functor and Monad. We will see finally what it takes to be a Monad in the next blog post. Happy coding until then! Cheers!

Thanks

- Said Marouf for reviewing the post.